Mogens Ballin

Belt Buckle designed by Mogens Ballin for his wife, Marguerite in 1900, celebrating his first born.

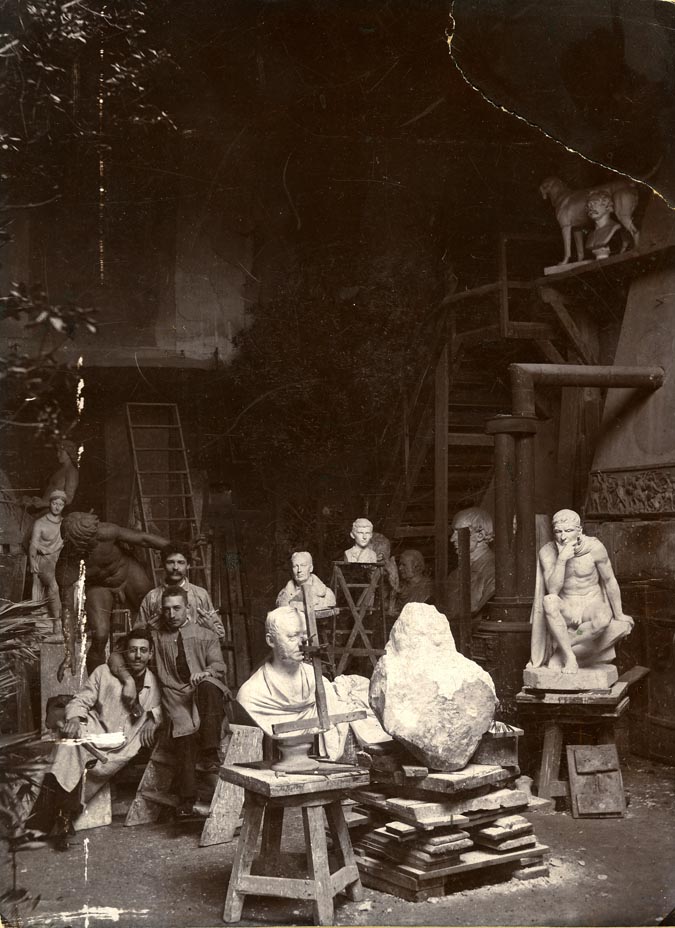

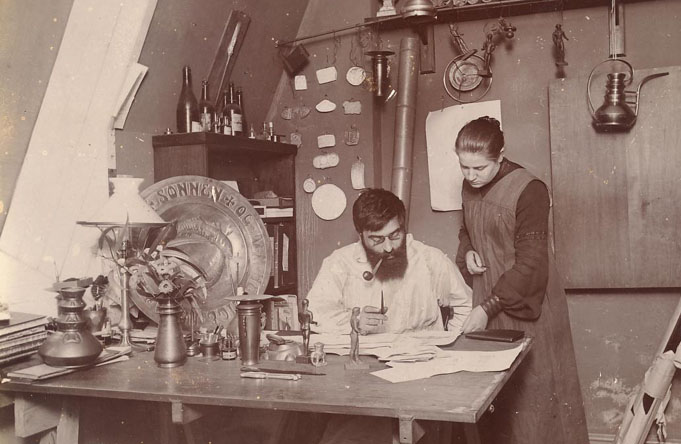

Mogens Ballin was born in 1871 in Copenhagen as the only child to a pair of well off parents whom fostered his early attraction to the arts, and trained as a painter. He was particularly attracted to the French styles of his time and his French studies with Gauguin's wife had allowed for him to take in the beauty and impressions of her artist husband as well as of fellow artists such as Van Gogh. Mogens Ballin had not been a strong artist himself, though he continued his efforts. In 1891, he met with another young artist from Holland, Jan Verkade, and traveled to Brittany where they joined the group, Les Nabis, who were inspired by Gaugin and painted in the style called Synthetism. It was here that he was exposed to the Catholic faith and during a trip to Italy they both converted. This caused a bit of struggle for Ballin's parents, whom were Jewish, especially with his mother. Upon returning to Copenhagen, Mogens Ballin met his wife, Marguerite, whom he married in January of 1899. During the same year, he started considering opening his own workshop, and with the help of a childhood friend, Benny Dessau, a brewery director, and began to work on producing small items of brass and metal in 1900 in an abandoned glassworks shop in Tuborg.

He set up the workshop around the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin of the English Arts and Crafts movement, focusing on creating small handmade items at a fair price, though his own personal style perhaps bore most resemblance to that of Thorvald Bindesboll, another influential Danish silversmith. During the beginning years, he also worked with Siegfried Wagner, whom primarily helped in developing models and shared in operating the business. Siegfried had been an assistant to both JF Willumsen and had worked at the Bing and Grondahl Porcelain factory, as well as having experience in teaching modeling and artistry, making up for what Ballin lacked. The immediately went about producing a large variety of pieces and entered them into an exhibition the following year.

The exhibition had gone quite well for both Mogens and Siegfried, and they showcased a number of pieces, most notable from the exhibition were a few of the belt buckles, and overall his style was praised as being both clean and simple while keeping with the times. Of all the exhibit present, Mogens Ballin had the largest selection, as he had demanded to show his complete collection or simply none at all. Not all were pleased with Ballin's work however, as they were with the more experienced Wagner, and the differences in execution and style were pronounced. Yet even still, they were both taken to complement each other well and approved of the partnership. During this first year, he had received a commission for a baptismal fountain for the Hellerup Church, which Wagner had assisted in designing. Executed in brass and tin, the font itself did not yield much profit, however Ballin was happy to do it, hoping for it to advertise his shop's abilities, which worked well as the orders began to file in and Siegfried began designing for more similar projects. It was also in 1901 that a young journeyman, Georg Jensen was taken on board, which helped to solidify their styles.

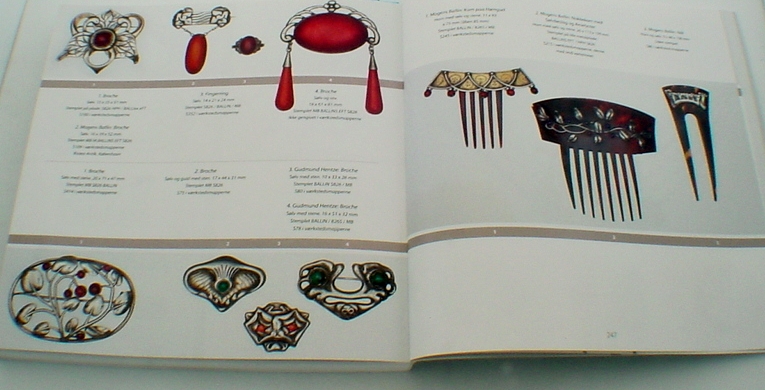

Also of note in regards to Mogens Ballin's shop is his openness to experimentation and new ideas. A deeply philosophical man, Mogens would often talk of various movements within the arts and kept in touch with trends. At the same time, we began to take an unconventional approach to his materials, experimenting with enamel and electroplating, which were very uncommon in Denmark at the time,and as such, were reserved from mass produced items. He would also try inlaying various base metals in others, such as brass in tin or lead within brass. He also was very open to bringing aboard new designers and artists and encouraged collaboration. Gudmund Hentze would also join the team, and also pursued JF Willumsen for designs, though the latter would prove unusable, as Mogens felt the designs submitted were too ornate, but also too costly to be usable for a mass production.

The following year, in 1902, an article on Mogens Ballin's workshop appeared in the “Decorative Arts” journal, written by his friend and author, Johannes Jorgensen, and with it, Ballin became introduced to the German audience. The article primarily focused on trends of the time and the innovation in Denmark's designers, and had listed Mogens Ballin alongside other such notable designers as Thorvald Bindesboll and Harald Slott-Moller, though praising them for their works in more base metals and the general democratization of design that Ballin promoted. The article appeared roughly the same time as an exibition in Berlin where a number of pieces were on display, which later also received high praise in Die Welt, a German publication.

Examples of Gudmund Hentze's work for the Mogens Ballin workshop

This introduction to an international market helped to grown the fledgling shop, and within a few years, the number of employees grew as the shop changed locations to Copenhagen. By the time Georg Jensen left to set up his own workshop, there were approximately 28 members of the staff, many of which would go on to establish their names within the world of silversmithing and the decorative arts in Denmark. Siegfried Wagner had left the shop in 1904, to take up another job as artistic director at a metalworks factory, but not before leaving a strong artistic impression upon the shop's line. Of those who had worked with him, Gudmund Hentze was probably the most opposite of Siegfried, with his rather haphazard and random approach to design.

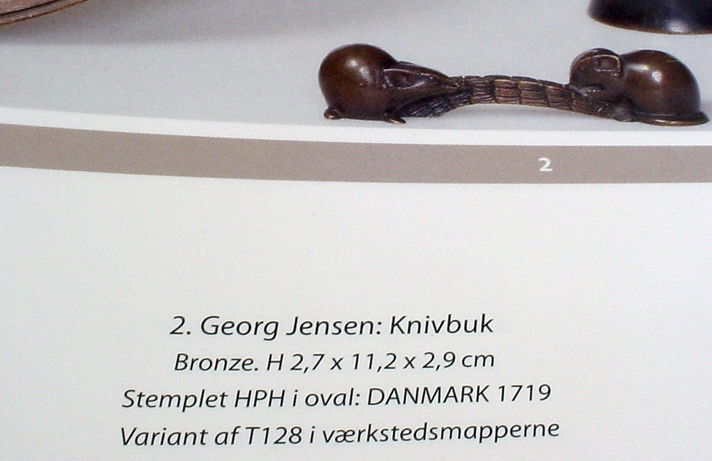

A knife rest, in bronze, designed by Georg Jensen for the Mogens Ballin workshop

Georg Jensen, on the other hand, became an incredibly important designer within the field of silver work, however, his designs for Mogens Ballin were almost opposite of the expected. He rarely submitted works in jewelry or in silver under the Mogens Ballin name (he was given the liberties to produce them under his own) but instead designed an assortment of items like nut crackers of tin or items in pewter and bronze. Georg Jensen's works also dramatically showed his desire and background in sculpture at the time, though it was Ballin's care with jewelry, creating and finishing jewelry pieces, that left the strongest impression with Jensen and would prove to be inspirational in the young silversmith's future. It was also with Mogens Ballin that Georg Jensen would first work with his lifelong friend, Johan Rohde, who approached Ballin about executing a set of silver cutlery.

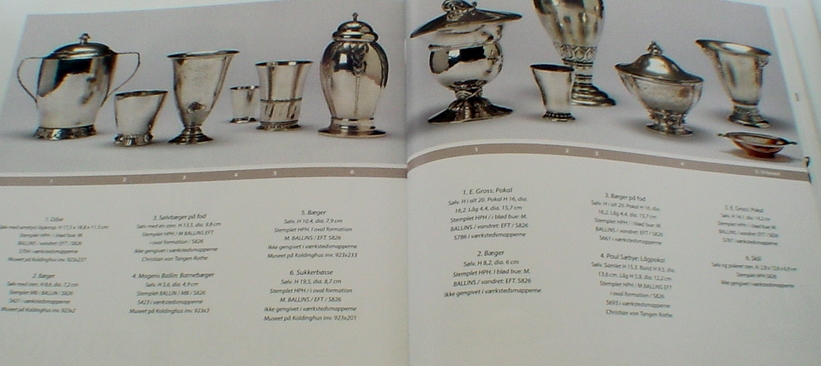

The shop itself did well, and in addition to his general production line, he also received a number of private commissions, including many inquiries for church silver. The pieces he designed for the monastery in Beuron was particularly well received, and also was written up in Die Welt. Unfortunately, it was with the loss of Siegfried Wagner as a business partner, that Mogens Ballin himself started to feel a longing once again for the painter's life. The demands of the business had been too strong upon him, leaving him with little time to himself, and despite the huge success of his products, the profits from them were minimal. Added to it, 1904 was the year he lost Georg Jensen, to which he was a firm supporter of the young silversmith, however, it had meant the loss of two crucial employees in the same year. In 1905, his wife's health had begun to take a turn for the worse, and a portion of 1906 had been spent n Italy, hoping for her recovery. Her health, however, continued to deteriorate, and in April of 1907 she had passed away. With her death, Mogens had lost all interest in the shop and sold it to H. P. Hertz after completing one of his final pieces, a perpetual candle for the abbey in Fiesole in honor of his wife.

H. P. Hertz, born from a long line of goldsmiths, had taken over the Mogens Ballin workshop just a year before completing his own training, and for the first year, took over production of the old Mogens Ballin models, only altering the hallmarks slightly to reflect the new ownership, before slowily introducing his own lines. He continued the tradition of introducing new artists but had refocused production to primarily silver products rather than base metals, (though tin items were still popular), and was more restrained in his experimentation in materials.

Just Andersen was amongst some of the young new faces at the reborn company, a man who had formally trained as a sculptor at the School of Danish Crafts in 1912, the same year he submitted a vase with chased flowers to the Mogens Ballin workshop, whicha copy of the vase still appears at the Museum of Decorative Arts today. Just Andersen in many ways carried on from Mogens Ballin, as he did with the copper altar that was promised by Mogens Ballin in 1900 with the birth of his first child, A promise that Just Andersen undertook with Ballin's mother's blessing in 1914, the year that Mogens Ballin passed away. To help with the work, Alba Lykke, Mogens Ballin's former chaser assisted. From this collaboration arose a budding romance, and in 1915 the couple was married. Unfortunately, the altar would be disassembled and the parts distributed in different areas of the church. This wasn't the only unfinished project of Mogens Ballin that Just Andersen would complete, nor the last, ties to his rich history. In 1914, upon his 80th birthday, the Bishop von Euch, reached out to Mogens Ballin to create a crosier of silver and ivory, and once again, Just Andersen would step into complete the master's task. Working with Jean Rene Gaugin, son of Paul Gaugin, the great artist whom Mogens Ballin originally studied art under, the piece was completed. Just Andersen himself would later set up his own workshop where he would design items in silver and gold, but also, most noteably in base metals like bronze and pewter, as well as his own experimental alloy, disko metal.

All of the pictures present in this article are sourced either from the Vejen Art Museum's website listed below or the Mogens Ballin book produced by the Vejen Art Museum.

Sources: http://www.vejenkunstmuseum.dk/Dansk/samlingen/mb/mb_historie.php

see mogens ballin’s grave stone

https://www.gravsted.dk/person.php?navn=mogensballin